We all know of the Black Matriarch. She is the engine that drives many of the novels in HBW’s 100 Novels Project, and in the larger body of African American writing. In literary works, she serves both the ghost of the past, conjured up to impart wisdom, and the tangible hand of the present, ever ready to guide, heal, and correct. Over one third of the novels in our project focus on Black women; and each feminine body is bound in the language of story telling, memory holding, and legacy.

We all know of the Black Matriarch. She is the engine that drives many of the novels in HBW’s 100 Novels Project, and in the larger body of African American writing. In literary works, she serves both the ghost of the past, conjured up to impart wisdom, and the tangible hand of the present, ever ready to guide, heal, and correct. Over one third of the novels in our project focus on Black women; and each feminine body is bound in the language of story telling, memory holding, and legacy.Leon Forrest’s Two Wings to Veil My Face focuses upon Nathaniel Witherspoon’s frantic capturing of his grandmother’s memories. Her words come in sermons, stories, dreams, and prayers; each word she gives him ties together a painful past to his fractured, current moment. Grandma Witherspoon serves as a cultural bridge, her stories lending a sense of understanding to lifetimes of racial trauma, disenfranchisement, and life.

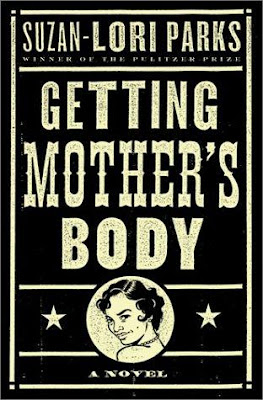

Getting Mother’s Body, by Suzan-Lori Parks uses the body of the protagonist’s dead mother as a medium through which to transmit stories of want, revenge, family, and the blues. Women, tied up in rumor, and housing stories to tell make this novel, each providing a different side to the gendered perils of migration, money, and what love actually looks like.

Gloria Naylor’s work, Mama Day is driven by Abigail, who serves as a root doctor and a repository of cultural and religious memory. She straddles contemporary life and the seemingly “old ways, working herb lore and Hoodoo into the life of her granddaughter, and in the process delivers to her truth and a new sense of faith.

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower details the life of a young woman, whose body serves as a vessel for both empathy and faith. Despite her young age, she leads a migration northward, towards hope and possible freedom, and begins in her community a new faith that encourages communal respect, peace, and the holding of cherished memory.

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower details the life of a young woman, whose body serves as a vessel for both empathy and faith. Despite her young age, she leads a migration northward, towards hope and possible freedom, and begins in her community a new faith that encourages communal respect, peace, and the holding of cherished memory. In each of these, and many more works, the feminine body serves both as a repository for cultural memory, and a vehicle that brings about social and religious change. Regardless of the gender of the author, their women characters function as additional storytellers, driving forward the other characters with tales linking the past to their current, racialized moments.

No comments:

Post a Comment